Supernormal Stimuli reflections: the ‘making of’

Supernormal Stimuli summary

Supernormal Stimuli describes the studies of Dutch biologist Niko Tinbergen, who sought to understand the root of animal instincts. Tinbergen’s experiments showed that instinctual behaviour could be triggered by specific sensations, such as colours, shapes or smells. Surprisingly, the animals would still respond with the full behavioural response even if the stimuli was exaggerated beyond realistic limits.

The comic observes that human beings are just as susceptible to supernormal stimuli as other animals. Indeed supernormal stimuli can be used to explain many of the problems we experience in our modern world of plenty, such as obesity. The comic concludes by pointing to an overlooked, but effective way of overcoming supernormal stimuli.

Niko Tinbergen’s experiments

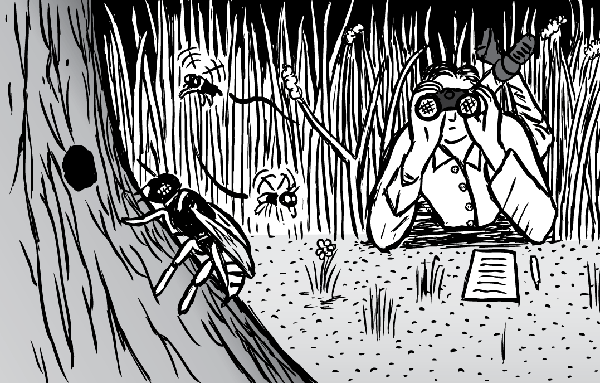

My interest in this subject purely came from the studies of Niko Tinbergen. I was intrigued by Tinbergen’s experiments which fooled animals into outrageous behaviours, including:

- Songbirds choosing to sit on enormous fluorescent blue eggs rather than their own small, pale blue eggs.

- Geese attempting to roll volleyballs into their own nest in preference to their regular-sized eggs.

- Male butterflies ignoring receptive females to instead mate with wingless vibrating dummies.

Although Niko Tinbergen’s experiments into animal behaviour are important in their own right, the way the concept doubles-back to incriminate humans is the icing on the cake. I had to draw a comic on it.

Legacy code in the genome

Humans are still struggling to wrap our heads around three facts which contradict our classical view of the world:

- Earth is not the centre of the universe,

- we were not created separately from the other life on Earth, and

- we are not exempt from the laws of nature.

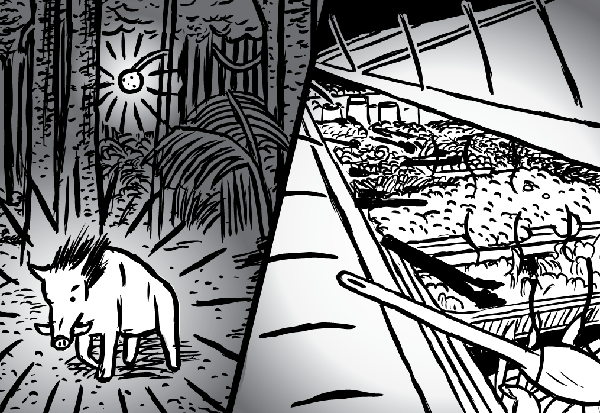

Our vulnerability to supernormal stimuli is evidence of our evolutionary heritage. Even though we live in a modern world of cities and electronics, we still carry genetic ‘legacy code’ to remind us of our past.

This legacy code (to borrow a computer programming expression), was written in a time when food was scarce, and our ancestors needed to feed on sweet, fatty and salty foods at every opportunity. The stronger our tongues registered these tastes, the more strongly we craved and sought out these foods.

It was also a time when predators and prey were too important to ignore. Moving shapes in the forest could reveal lethal adversaries, potential mates, or the next meal ticket. Because of this, the primitive ‘orienting response‘ instinct evolved to make us freeze and stare at movement. We kept motionless until we were sure the object was not a threat, and we were sure how to respond.

Both of these instincts are hijacked in the modern day food court. We tuck into foods far sweeter, fattier, or saltier than what our ancestors could have found in the wild. Meanwhile, the orienting response draws our eyes to the flickering images of televisions scattered throughout the room. The supernormal of the modern world surrounds us.

Artwork

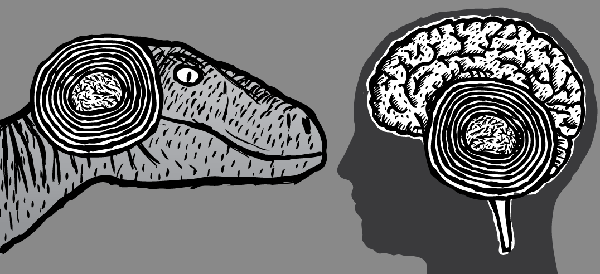

The experiments of Niko Tinbergen were an interesting enough concept to tie the comic together, but I needed another hook. The answer: dinosaurs!

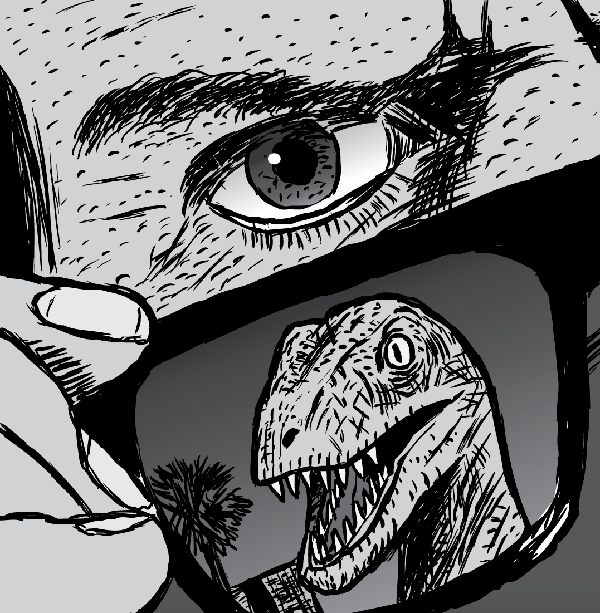

Dinosaurs are always fun to draw, but I actually came up with a legitimate way to feature them in Supernormal Stimuli via the sections on the ‘reptile brain’. Though the reptile brain concept may not be strictly true, it gives us a simple way of understanding how brains evolved from common primitive ancestors.

Beyond the dinosaurs, the comic is quite a whirlwind of activity, jumping from Tinbergen’s experiments to primitive Africa, and then to a modern city shopping mall dripping with supernormal stimuli. I’m especially proud of the final sequence: I hope we can all learn to be like “Rowdy” Rodin’s The Thinker, opening a can of kick-ass on the supernormal stimuli raptors which surround us.

For the trainspotters: Supernormal Stimuli was my first comic completed via graphics tablet and handwriting font. My earlier comics such as St Matthew Island and Purpose were drawn with pen and ink, and handwritten lettering.

Different world, same brain

It’s interesting to think of the societal changes that have occurred even in my short lifetime. When I was young, before email, we checked the mail once per day. Now we check for messages throughout the day. When we left the house, we were uncontactable. Now our mobile phones follow us everywhere. Large changes are happening to our cities, food and technology, yet genetically we are essentially identical to our 10,000 year-old ancestors.

I wonder what the implications of these shifting sands are. Whether the human mind is adaptable enough to function in situations far beyond its original purpose. Or, alternatively, whether we lose a little something the further we venture from our roots.

As always, my comic only scratches the surface of this fascinating subject. My comics can never provide a total summary of a subject, nor can they explain all the nuances and debates that surround the topic. But hopefully through 20 pages of comics, Supernormal Stimuli gives readers a distilled primer about an interesting subject that affects us all.

Comments